Bruce Trinque had many interests - the works of Patrick O'Brian, the Civil War, Custer and the battle of Little Big Horn, the Titanic, and translating anew such historic classics as Beowulf and books of the Illiad.

He especially loved the Patrick O'Brian Aubrey/Maturin novels, researching and writing about many topics from those books. His death in 2013 after a short illness saddened his many friends across the world. His words and thoughts, however, live on in his writings such as this one.

The Mauritius Campaign by Bruce A. Trinque

(copyright 1998)

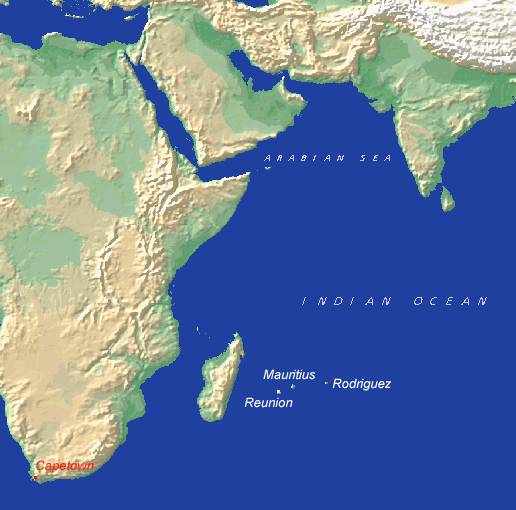

After sixteen years of nearly continuous warfare against Revolutionary France and the Emperor Napoleon, the Royal Naval had not yet swept their foes wholly from the seas. Despite great English victories over enemy fleets at the Nile and Trafalgar and although British warships had won numerous single-vessel and squadron actions, France still retained her capacity to harry the long, vulnerable sea lanes which connected England to her scattered colonies. Nowhere was this threat greater than in the vast, almost empty western Indian Ocean. There, based at the island of Mauritius, French naval units and privateers -- privately-owned armed vessels operating under legal sanction -- sailed out to prey upon British ships carrying home rich cargoes from India and the Orient.

Mauritius, also known as the Ile de France, was nicknamed "the Gibraltar of the East" for its reputed strength and also for its strategic location near the two great trade routes around the Cape of Good Hope to India and to the East Indies. The island provided a way station for any expedition sailing from distant France to either the East Indies or to India, intent on making mischief for the British there. Arthur Wellesley, later the Duke of Wellington, had declared that India would not be secure until Mauritius was conquered, but thus far France's Indian Ocean island possessions had remained untouched. Primarily this was because British resources had been stretched too thin, always assigned to higher priorities, but inter-command rivalries had also worked to thwart earlier plans.

Now, in 1809, Britain finally began to move towards eliminating this last threat. Royal Navy efforts would be based at Cape Town on the southern tip of Africa, still nearly 3000 miles from "the Gibraltar of the East." India, a source of soldiers and additional naval support, was even further distant. Any British commander operating off Mauritius would have to rely upon his own resources, out of communication with his superiors for weeks or months at a time.

The first task would be to tighten the blockade, keeping French raiders in port. Blockade operations were among the most arduous of all duties facing the Royal Navy. Warships, like any sailing vessel, were captives of currents, tides and, above all else, the wind. Guarding a port required the blockading ships to sail ceaselessly back and forth, staying close enough to the harbor to prevent escape, but keeping far enough out to sea so that an unfavorable shift in wind direction wouldn't drive the ships on to the shore and destruction.

Wind direction was critical. Square-rigged warships could only sawtooth their way slowly forward when the wind was against them, sailing several miles laterally for every mile gained ahead. In storm conditions, vessels couldn't do even that and had to run before the wind, leaving their blockade stations many miles behind, their enemies free to escape undetected.

Any blockade of Mauritius was complicated by the existence of two excellent ports: Port Louis on the northwest side of the island and Grand Port on the southeast. Arriving French ships, guided by signals from high ground, could avoid British vessels to enter whichever port was at present unguarded. If necessary French ships could also find refuge at St. Paul's Bay or one of the smaller harbors on the island of Reunion, also known as Bourbon, 150 miles west of Mauritius.

Commodore Josias Rowley commanded the squadron of British ships sent to cruise off Mauritius. Although the Royal Navy had blockaded the island intermittently for years, this activity became reasonably effective only in 1808. By the end of that year French naval forces in the area were reduced to a single small corvette and one elderly vessel too battered for further operations.

Rowley had to withdraw his ships during the hurricane season during the early months of 1809, leaving Mauritius unguarded until the end of March. When he returned, Rowley found he had to contend with a far more formidable enemy force than the year previous. Late in 1808 Napoleon had despatched the "Division Hamelin" to reinforce Mauritius. Four new frigates -- warships combining speed with powerful broadsides -- slipped individually out of French mainland ports and made their way to the Indian Ocean island to combine under the command of Commodore Jacques Hamelin. By the time Josias Rowley could return to his blockade station, the French frigates had already departed in search of British prizes.

Rowley's squadron of one superannuated ship-of-the-line, an elderly 50-gun ship, three frigates and two smaller vessels was nominally superior to Hamelin's forces, but wholly inadequate to maintain a blockade while searching for the French raiders at the same time. The British commander could only guard the waters around Mauritius and Reunion, hoping to intercept the enemy frigates when they returned to port. In any battle Rowley would have to rely strongly upon the skill and experience of his crews, because the French frigates were bigger and more heavily armed than their British adversaries.

Rowley was faced by problems with his officers as troubling as his insufficient strength. Captain Robert Corbet of the frigate Nereide had a dark reputation as a brutal disciplinarian. His crew had recently circulated a petition for his court-martial and, when the start of the trial was delayed, an abortive mutiny broke out. A court-martial found Corbet not guilty of all charges, except using "sticks of an improper size" to beat his men, for which he received a mild reprimand. Ten of the Nereide mutineers were sentenced to death, although nine were subsequently pardoned. Within a few days of his acquittal, Corbet found himself sitting on the panel in judgment over Nesbit Willoughby, commander of the sloop Otter, being tried on similar charges of cruelty. Willoughby, not surprisingly in those circumstances, was declared innocent.

Commodore Hamelin's ships met with marked success in their cruises across the Indian Ocean. Five rich Indiamen -- large merchant vessels -- were taken. Neutral American ships, safe from British interference, carried the fruits of Hamelin's cruises from Mauritius. Combined with the loss of five other Indiamen foundered at sea in storms and three others wrecked, the captures meant the British East India Company had lost thirteen of its ships during a single year, an unprecedented disaster. The Company and its stockholders howled in dismay and demanded action.

Now, Rowley moved to aggressively test French strength. A first, tentative step had already been taken early in 1809 when a British expeditionary force from Bombay seized the island of Rodriguez, nearly 400 miles east of Mauritius. Although virtually uninhabited, Rodriguez would be a source of water, wood, and fresh vegetables for Rowley's blockading squadron, easing their supply burden.

Having taken aboard at Rodriguez a force of a few hundred soldiers commanded by Lt. Col. Henry Keating, Rowley feinted towards Mauritius, then dashed westward to Reunion. The main port of St. Paul, protected by 125 pieces of artillery, was too formidable to be approached directly from the sea. On September 21, Rowley put the soldiers ashore about seven miles west of the town. They were accompanied by a landing force of sailors and Marines led by Commander Willoughby. Keating marched rapidly overland and took the French artillery batteries against light opposition, opening the way for Rowley to bring his ships into the harbor.

The French frigate Caroline and two of her Indiamen prizes in the harbor were captured. Storehouses were set afire. To the chagrin of Rowley, his officers, and his men, one of warehouses burned contained silk worth 500,000 pounds sterling. In the Royal Navy, as in all other naval forces of the day, captured ships and property were sold and the money obtained then distributed amongst the victorious officers and men. Rowley's share of one-sixth of the £500,000 pounds would have made him wealthy, while even the lowest seaman would have received a portion equivalent to months of pay.

Capture of St. Paul, by Thomas Whitcombe

The attack was only a raid, intended to discomfort the French. Although the defenses of St. Paul had been overcome with little resistance, strong French land forces were reported elsewhere on the island and were expected to counterattack. A more rash commander might have tried to turn the raid into a full-fledged conquest and occupation, but Rowley decided that the risks of further action without reinforcements were too great. Having temporarily disabled the French artillery defenses by "spiking" the cannons -- driving spikes into the guns' vent holes to prevent them from being fired -- the British boarded their ships and sailed away.

Robert Corbet was now given command of the captured Caroline to take the frigate back to England. Any relief the Nereide's crew may have felt at the removal of their brutal captain must have been tempered by the appointment of his successor -- Nesbit Willoughby, with his own reputation as a harsh disciplinarian.

Having transported Keating's soldiers back to Rodriguez, Rowley returned to the tedious duty of blockading Mauritius. French depredations against Indian Ocean shipping continued. In November alone they captured three Indiamen, a British sloop-of-war, and the Portuguese frigate Minerve, soon to be added to Hamelin's squadron to offset the loss of the Caroline.

The early months of 1810 saw Rowley again forced to withdraw to the Cape of Good Hope due to storms, but British ships returned to their blockade duty by April. Five English frigates -- the old ship-of-the-line and 50-gun ship had been ordered home for repairs -- now faced five French frigates, including the newly arrived Astree. Rowley began probing at French defenses on Mauritius. The energetic Willoughby, a specialist in landing operations, took every opportunity to bring his men ashore on isolated beaches and islets to drill them in small arms practice and military tactics. One of these training exercises nearly proved fatal to the dashing, if harsh commander. In June a musket exploded in Willoughby's face, shattering his jaw and ripping a gruesome wound in his neck.

Another attack on Reunion was planned, but this time with the intent to permanently occupy the island. Rowley temporarily withdrew his ships from the waters of Mauritius and convoyed a force of 4000 soldiers from Rodriguez. The landings were carried out in early July under the supervision of Nesbit Willoughby, his painful wounds bound with bandages. Resistance was minimal and the island quickly capitulated.

Nesbit Willoughby

Rowley decided to direct operations from St. Paul on Reunion, sending most of the British warships, under the command of Captain Samuel Pym, back to Mauritius. Pym was faced with the old problem of dealing with two French ports on opposite ends of the island: Port Louis on the northwest and Grand Port on the southeast. Capturing the Ile de la Passe, a small fortified island at the southern entrance to the long, twisting channel to the harbor of Grand Port, would greatly simplify the task. With the Ile de la Passe in British hands, Grand Port would be effectively closed to the French. Leaving Captain Henry Lambert in the Iphigenia off Port Louis to continue to blockade the harbor, Pym took the frigates Sirius and Nereide and a brig to make his attack.

On the 10th of August Pym attempted a surprise landing on the Ile de la Passe, but the French garrison discovered the approaching British, prompting Pym to temporarily withdraw to rejoin Lambert. Pym, however, had no intention of abandoning his plan. To lull French anxiety, he now split his forces, with Pym himself taking the Sirius around the north side of the island, while Nesbit Willoughby with the Nereide and the brig sailed along the southern coast. The Iphigenia remained on blockade off Port Louis, keeping watch on three French frigates. Pym and Willoughby were supposed to unite before attacking the Ile de la Passe again, but Pym arrived first, on the 13th, and decided to attack immediately. He sent a landing force in small boats and seized the island by surprise. Willoughby arrived the next day, dismayed at seeing the prize already taken without his participation.

While Pym withdrew the Sirius back to join Lambert at Port Louis, Willoughby was left in charge of the captured fort and his own frigate Nereide with orders to engage in raids along the nearby the coast and to distribute propaganda in the hopes of fomenting unrest. Only a few days later, on August 20th, Willoughby spotted a squadron of several vessels sailing towards the harbor. The French frigates Bellone and Minerve and the small corvette Victor were carrying in two East Indiamen prizes.

Willoughby decided to entice the French squadron under the guns of the Ile de la Passe. He ordered French tricolors raised above the fort and his frigate anchored nearby, a common and honorable ruse of war. A rigid code of conduct demanded, however, that the true colors be hoisted before the actual start of combat. When the unsuspecting ships neared the British frigate, Willoughby ordered the French ensign lowered and the British flag raised, and then opened fire. The French corvette, shocked by the unexpected attack, quickly surrendered and anchored.

In the fort on the Ile de la Passe, however, disaster struck. As the huge French banner descended in preparation to opening fire, a gust of wind caught it and whipped the flag across an open flame. The cloth caught fire and ignited a gunpowder charge held ready near a cannon for rapid reloading. In a chain reaction, piles of bagged charges stacked behind the line of guns along the rampart exploded. In an instant, several guns were disabled and the cannon crews killed, wounded or stunned.

In the confusion, the Victor quickly raised its colors again before the British could take possession and set sail. The French ships, except for the Windham, one of the captured Indiamen, plunged onwards the inner harbor, running past Willoughby's shaken artillerymen. The fort's guns fired wildly, doing little damage to the French ships. The Windham turned out to sea, seeking to reach safety at Port Louis. Willoughby could only watch in frustration as the other French ships continued up the channel to find refuge in Grand Port.

On the next day the Windham, in the hands of its 30-man French prize crew, stumbled on to Samuel Pym's Sirius in company with the British frigate Magicienne. The Indiaman attempted to find safety under French shore batteries, but Pym sent a boarding party in small boats to capture the Windham and sail her out from under the guns. Learning now of the arrival of the French squadron at Grand Port, Pym dispatched the Windham to Rowley at Reunion while he himself sailed to reinforce Willoughby. Pym sent the Magicienne to pick up Lambert in the Iphigenia , keeping watch over Hamelin's force of three frigates in Port Louis.

The day after the French squadron had successfully entered Grand Port, Willoughby sent a messenger into the harbor to demand the return of the Victor, arguing that the French corvette had violated the rules of war by escaping after lowering its flag. Not surprisingly, the French commander declined to surrender again.

Pym in the Sirius arrived off Grand Port on August 22. Never a man to counsel delay, Willoughby hoisted signal flags above the Ile de la Passe: "Ready for action. Enemy of inferior force." Without hesitation, Pym headed towards the entrance to the harbor. The Sirius and Willoughby's Nereide would sail directly into Grand Port to attack and subdue the French ships anchored there, disregarding the protecting shore batteries. As Pym neared the channel entrance, however, the Sirius struck a shoal and grounded. Willoughby abandoned the attack and went to assist Pym.

The Sirius had not been badly damaged and was refloated the next morning. Shortly afterwards, Henry Lambert's Iphigenia and the Magicienne were seen in the approach. Now, with a force of four frigates, Pym renewed the attack. His plan was to force his way deep into the harbor and close with the anchored ships, steering if possible between the vessels to engage them from both sides at once, as Lord Nelson had done so successfully at the Nile.

Willoughby in the Nereide led the column of ships into the mouth of the channel. Under the guidance of a native pilot and with the knowledge of local conditions gained through his raids, Willoughby got the Nereide safely through the narrow, shoal-edged channel. Pym, however, chose not to follow Willoughby directly, but instead steered a course further to the northeast. Without warning, the Sirius ran hard on to a coral rock. The Magicienne continued along the channel but then she too ran solidly aground. The Iphigenia dropped anchor in several fathoms of water, abandoning the attempt to close with the French squadron.

The Nereide alone carried on towards the French ships, anchored bow-to-stern in a line parallel to the shore. Willoughby came under fire from the vessels and the land forts as he approached. He aimed the Nereide for the gap between two of the ships, intending to anchor there, his port broadside sweeping the stern of one frigate and the starboard raking the bow of the other. The French ships were too close together, however, for Willoughby to penetrate the gap, and he was forced to turn aside to anchor and engage the Bellone, broadside to broadside. In the meantime, the Iphigenia opened fire on the French vessels from a greater distance.

The two French frigates and the Indiaman prize tried to get underway but the Bellone and the captured merchant ship ran aground. For a few minutes it seemed as if the daring British attack, despite the misfortune of the vessels in the narrow channel, might succeed. Then, Willoughby's frigate also grounded in shallow water and became a stationary target. As darkness fell, the fighting in Grand Port's harbor continued into the night.

His ship battered by uncounted hits, most of his men casualties, Willoughby tried to surrender and was relieved when, after midnight, the French guns fell silent. At daybreak, however, the Bellone resumed fire. Willoughby discovered himself unable to lower the Union Jack at the peak of his mainmast. Probably the halyards had been cut and became snagged during the desperate fight, although it was later claimed that someone had nailed the colors to the mast in a gesture of defiance. Whatever the cause, the flag continued to draw enemy fire. Finally, Willoughby ordered the mainmast cut down and the enemy's fire ceased. Of the Nereide's 281-man crew, about 230 had been killed or wounded. Willoughby himself lost an eye when struck in the face by a large, jagged splinter, the chief cause of casualties during combat on wooden ships.

The French now turned their attention to the three British warships still in the channel, two of them stranded on shoals. Pym signaled Lambert to withdraw the Iphigenia and come to his aid. Unable to sail back up the channel, Lambert resorted to "warping" to move his vessel -- carrying an anchor forward in a boat, dropping the anchor to the bottom, and laboriously pulling the ship along the attached cable until the anchor could be retrieved and the process repeated again.

All through the 24th, the Iphigenia laboriously made its way up the channel while the French continued to fire on the enemy ships. Shortly before midnight, the British abandoned the grounded Magicienne and blew it up to prevent capture. On the following morning, two days after the attack had begun, the Sirius too was abandoned and destroyed. Only the Iphigenia remained afloat, still slowly warping its way up the channel. Not until the 27th, after days of back-breaking labor, did the British frigate finally reach the presumed safety of the Ile de la Passe. Then, to the dismay of Pym and Lambert, the three frigates of Commodore Hamelin's squadron appeared off-shore. Hamelin had sailed out of Port Louis after Lambert's withdrawal and, once he learned of the action at the Ile de la Passe, headed towards Grand Port. He now summoned the British to capitulate. The following morning, with no prospect of relief, Lambert and Pym surrendered.

Battle of Grand Port, by A. D'Etroyer, 1812

Wooden ships, in comparison with their iron and steel successors, were highly resilient vessels. Given an adequate stock of replacement spars and rigging cordage, even after heavy combat a wooden warship could often be restored to good sailing and fighting condition through the efforts of its own crew, without resorting to shore facilities. Furthermore, the damage done by solid cannon shot generally did not threaten to sink a ship. Masts and men might fall, but damage to the hull below the waterline was often negligible. Except in cases of extraordinary accident, such as an exploding magazine, naval actions of the era typically ended with surrender rather than sinking. Captured warships were frequently taken into the victor's navy, sometimes after only a few days of repair. The Royal Navy boasted such a record of success that many of His Majesty's ships had begun their lives in French or Spanish shipyards. Willoughby's Nereide was one such former prize. This time, however, fortune did not favor the Royal Navy and the British Iphigenia, its name slightly altered to "Iphigenie", was quickly added to Hamelin's squadron. The Nereide, though, was too badly shattered for rapid repair, and the Bellone and the Minerve had suffered too much damage in Pym's attack to go to sea at present.

The Windham arrived at St. Paul's Bay, bearing word of the arrival of the French squadron at Grand Port. Rowley sailed in the Boadicea for the scene of the action, but the usual adverse winds delayed his arrival until after Iphigenia's surrender. The Venus and Manche chased Rowley back to St. Denis, near St. Paul, before themselves proceeding to Port Louis to join the Astree.

In one catastrophic engagement, the balance of naval power had shifted heavily to the French. Josias Rowley now had but a single frigate to counter Hamelin's four, not counting the three other frigates in French hands to be repaired. Despite the odds against him, Rowley immediately set out again for Mauritius, seeking some means of rectifying the situation. He sent the small transport Emma to cruise off Rodriguez to warn any passing British vessels of the danger from the French squadron while he himself in the Boadicea looked in at Grand Port again. Finding the captured Iphigenie already gone and unable to accomplish anything with his single ship, Rowley returned to St. Paul, arriving there on September 11.

Unknown to the British commodore, a familiar figure was about to return to the scene. The Admiralty in London had dispatched during the spring the frigate Africaine, bearing orders for the capture of Reunion and Mauritius. Command of the ship was given to Captain Robert Corbet. The Africaine's crew, alarmed by tales of his brutality, at first refused to go to sea with their new captain, until convinced by Admiralty representatives that Corbet would not be removed from command and that they would be punished if they did not end their protest.

On the Africaine's voyage to the Indian Ocean, Corbet resumed his usual severe discipline methods. He conducted seemingly endless drills to perfect sail-handling which he considered to be the essence of naval efficiency, but he utterly neglected cannon practice. On September 9 Corbet arrived at Rodriguez and, upon learning of the disaster at Grand Port, immediately set sail to the west. He drove ashore a French dispatch vessel on the north shore of Mauritius and, on the morning of the 12th, arrived off St. Denis on Reunion only to find the French Astree and Iphigenie with a brig cruising off the island. Corbet landed several men wounded in the attack on the dispatch boat.

Rowley at St. Paul, learning by courier of the Africaine's arrival, immediately put to sea in the Boadicea, with two smaller vessels, in pursuit of the French ships. When Corbet saw the British squadron, he too set sail. The three French warships, unwilling to confront the combined British forces, fled towards Mauritius.

The chase continued into the night, with the Africaine drawing ahead of the other British vessels. Early in the morning the Africaine, now several miles from Rowley's ships, came up to the two French frigates. Although outnumbered Corbet attacked, apparently concerned that the French would reach the safety of Port Louis before the other British ships could join him. Experience had taught the Royal Navy to expect victory in single-ship actions against anything other than overwhelming force, and even two-to-one was not considered impossible, but Corbet's cruelty and obsession with sail-handling now exacted a cost. After an action of two-and-a-half hours, the Africaine -- hampered by poor gunnery by the ill-trained and disaffected gun crews and practically dismasted -- hauled down its flag. Robert Corbet had been mortally wounded by an enemy cannon ball, although rumors would later spread that he had been shot by his own men.

Rowley's Boadicea had become separated from her two smaller consorts during the night, so the British commodore delayed advancing on the French frigates and their disabled prize until he had reunited his squadron. The British commodore, unlike many of his contemporaries, understood the necessity to balance determination with prudence. The French commander, upon approach of the three British ships, abandoned the Africaine and withdrew. Rowley took the re-captured frigate in tow and returned to St. Paul's Bay, where he anchored on September 15. Within hours, however, the Boadicea and her two smaller escorts again set sail in search of the Astree and the Iphigenie which had cautiously followed the British squadron back to Reunion. After three days of inconclusive maneuvering, Rowley anchored once again at St. Paul, while the two French frigates returned to Port Louis.

In the meantime, the British frigate Ceylon sailed from India, carrying Major-General Sir John Abercromby, Commander-in-Chief at Bombay and the designated commander of the planned expedition to conquer Mauritius. The Ceylon looked in at Port Louis on September 17, hoping to find Rowley's squadron. Instead seeing only what appeared to be a strong French force in the harbor, the British frigate turned its course towards Reunion. Commodore Hamelin in the Venus, accompanied by the corvette Victor, set out in pursuit of the British ship. Shortly after midnight, Hamelin caught up with the British frigate. A sharp action left the Ceylon unable to maneuver and at the mercy of her two opponents. The British commander struck his flag.

In the morning light Rowley saw the French ships and their prize off Reunion and again put to sea with the Boadicea and her two smaller escorts, although the battered Africaine was still not ready for action. Upon the approach of Rowley's squadron, the Victor first attempted to tow the Ceylon to safety but, finding this to be impossible, the French corvette cast off the prize and fled. The Ceylon's crew quickly rehoisted the British ensign while the Boadicea closed with Hamelin's Venus. After only ten minutes of fighting the battle was done, the French tricolor hauled down in surrender. General Abercromby and his staff were found aboard, unharmed.

For the next three weeks British sailors, assisted by soldiers of Reunion's garrison, labored intensely to refit the three frigates taken by Rowley. Their task was lightened by the fortunate discovery that the Venus carried a large quantity of naval stores recently captured in a British supply ship. In a remarkably short time, Rowley had all four of his frigates, Boadicea, Africaine, Ceylon, and Venus, ready for combat. The balance of power had been more than restored. Against his force the French could bring at most three frigates. More importantly, French morale had crumbled under the determined counterpunches of the indomitable Josias Rowley and the loss of their own naval commander in the last battle.

In early October, Admiral Albemarle Bertie arrived from his headquarters at Cape Town to take command of the anticipated final blow against Mauritius. The ground had been well prepared by Commodore Rowley. At the end of November, an overwhelming force of British soldiers landed on the island and on December 3, 1810, the French defenders surrendered.

The last act in the conquest of Mauritius, however, came months later. Word of the island's fall still not having reached France by February of 1811, three frigates carrying reinforcements and supplies left Brest for the Indian Ocean. They arrived off Grand Port in early May but, finding the island to be in British hands, then sailed west to Madagascar. A pursuing Royal Navy squadron captured two of the frigates there. Only the third vessel, deserting its consorts, escaped to return to France, where its commander was tried for misconduct and dismissed from the service.

In recognition of his "zeal, judgment, perseverance, skill and intrepidity" so warmly praised by Admiral Bertie, Josias Rowley was given the honor of carrying back to England the despatches announcing the capture of Mauritius. In 1813 he was created a baronet and was promoted to Rear-Admiral the following year. Rowley held several important commands after the war and was a Vice-Admiral at the time of his death in 1842.

Although Nesbit Willoughby's wisdom in precipitating the battle at Grand Port was questioned by some, his desperate defense of his ship won him wide praise and he was honorably acquitted by the court-martial which automatically followed the loss of any ship. Never again employed on active naval service, Willoughby volunteered his services to the Russian Army during Napoleon's invasion in 1812. Captured once more by the French, he was sent to France as a prisoner, but later escaped. Twice knighted, Willoughby died a Rear-Admiral in 1849.

Captain Henry Lambert of the Iphigenia was also absolved of any blame in the loss of his ship at Grand Port and in 1812 was appointed to the command of another frigate, one of the French prizes captured at Madagascar. On December 29 of that same year, he confronted a new enemy in the waters off Brazil. The American frigate Constitution overwhelmed Lambert's ship, Java, in a short, furious battle. Lambert was mortally wounded and his ship surrendered to be destroyed the next day, too badly damaged to be taken off as a prize. The Royal Navy had not yet learned one of the primary lesson of the Mauritius campaign, that a simple courageous willingness to do battle against superior strength was not enough to guarantee victory. Few commanders were the equal of Josias Rowley, able to skillfully create the conditions needed for victory, even when faced with daunting odds.

Suggested Reading: The best modern history of the naval campaign against Mauritius can be found in C. Northcote Parkinson's War in the Eastern Seas: 1793-1815. A highly authentic fictional account is given in The Mauritius Command, one of Patrick O'Brian's superb nautical novels about the exploits of Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin of the Royal Navy.

-----------------------------

Bibliography

William Laird Clowes, The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Present (AMS Press, Inc., New York, 1966) Volume 5

William James, The Naval History of Great Britain from the Declaration of War by France in 1793 to the Accession of George IV (Richard Bentley & Son, London, 1886) Volume 5

C. Northcote Parkinson, War in the Eastern Seas: 1793-1815 (George Allen & Urwin Ltd., London, 1954)

Anthony Price, The Eyes of the Fleet: A Popular History of Frigates and Frigate Captains, 1793-1815 (Hutchinson, London, 1990)

Leslie Stephen and Sidney Lee, editors, The Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press) Various volumes

Richard Woodman, The Victory of Seapower: Winning the Napoleonic War, 1806-1814 (Chatham Publishing, London, 1998)